Catherine of Siena Levels of Glory if a Man Could See Heaven He Would Never Sin Again

Nobody loves a listsicle like late medieval Christianity. You know the 7 mortiferous sins; now come across the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, the half-dozen sins against the Holy Spirit, the four sins that weep to heaven (simply one of which is silent)…and in belatedly medieval didactic literature, enumerated lists are everywhere. Fortunately, twenty-first century versions like "10 Badass Medieval Women" tend to have slightly more cross-cultural appeal. Just a funny thing happens when you start reading through those lists: they tin exist virtually equally repetitive equally their medieval ancestors. They feature a few sentences or a short paragraph about Hildegard of Bingen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Sitt al-Mulk, maybe Jeanne la Flamme or Catherine of Siena.

And so the Medieval Studies Research Blog is proud to introduce our new, not-listsicle serial on Medieval Women You Should Know. It aims to use the stories of women effectually the medieval globe to illuminate life in the Middle Ages more broadly. That might mean an examination of the transmission history of a adult female-authored text, a look at the relationship dynamic between two women, or the traditional contextualized-biography approach.

Yes, "badass women" will be represented, like the at present-nameless mother of eleventh-century vizier al-Afdal, who went undercover as the mother of a deceased soldier to root out opposition to her son'south dominion [one]; or Juliana Peutinger, the three-year-onetime who recited a Latin oration to the Holy Roman Emperor in a premodern version of Toddlers & Tiaras. [ii]

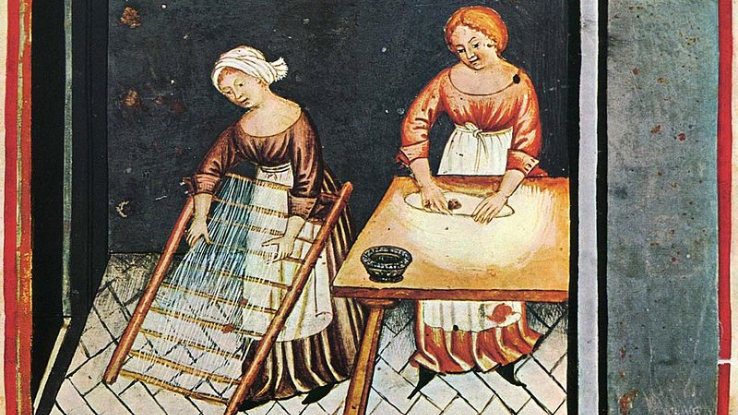

But in that location are likewise the women known to us only past chance, whose existence is folded into phenomenon collections or revenue enhancement registers: women extraordinary only to themselves and their loved ones. Through their eyes and lives we see through the bright lights to the texture of medieval social club. As Katherine Anne Wilson points out, we should non look at a photo of a gorgeous tapestry and call up just of its primary, but too the women who spun the thread, the women who cooked meals for the craftsmen and cared for their children. [iii]

To illuminate women great and modest also offers the chance to highlight one of my favorite things about medieval studies and our scholars: that is, the ability to draw an entire life story out of a line or two in a courtroom case, a papal petition. Who needs a detailed biography when you can read that nine-year-old Mary de Billingsgate drowned in the Thames, and reconstruct her single mother's efforts to raise a child, manage a household, and try to earn a living on her own? [four]

And finally, equally Medieval Studies Inquiry Blog pageview statistics bespeak that the blog is taking on a double life as a medieval studies resources blog, I hope to pay forward a debt from the very kickoff of my graduate work. When I first barbarous in love with medieval women mystics, there was an astonishing online resource chosen "Other Women'southward Voices." It collated biographical data, links to online scholarship, and excerpts from the writing of women from artifact through the early on 1700s. Even more than the Classics of Western Spirituality series and the index of Bynum's Holy Feast and Holy Fast, Other Women's Voices was my entry to what was for me an unknown and wondrous world. While the Medieval Studies Research Blog has no intentions of replicating that site (which lives on through archive.org's Wayback Machine), we promise the posts in this series can provide a similar sort of inspiration: not an end, just a beginning.

Cait Stevenson

PhD in Medieval Studies

University of Notre Matriarch

—

[1] Della Cortese and Simonetta Calderini, Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam (Edinburgh University Press, 2006), 37.

[two] Jane Stevenson, Women Latin Poets: Language, Gender, and Dominance from Antiquity to the Eighteenth Century (Oxford Academy Press, 2005), 229-230.

[3] Katherine Anne Wilson, "The Hidden Narratives of Medieval Fine art," in Whose Middle Ages? Teachable Moments for an Ill-Used Past, ed. Andrew Albin et al. (Fordham University Press, 2019).

[4] Reginald R. Sharpe (ed.), Calendar of Coroners Rolls of the Metropolis of London, A.D. 1300-1378 (Richard Dirt and Sons, Ltd., 1913), 252-253.

In a alphabetic character (T266/G89) that St. Catherine wrote to Raymond of Capua, dated to well-nigh February 17, 1376, she develops an extended analogy betwixt a soul learning to dearest God and a person approaching the body of water.[i] She tells Raymond:

For when a soul sees not self for self's sake, merely self for God and God for God, inasmuch as he is supreme eternal Goodness, […] information technology finds in him the image of his creature, and in itself, that image, information technology finds him. That is, the love a human sees that God has for him, he, in plough, extends to all creatures, and and so at in one case feels compelled to honey his neighbour every bit himself, for he sees how supremely he himself is loved past God when he beholds himself in the wellspring of the sea of the divine Essence. He is and then moved to love cocky in God and God in self, like a man who, on looking into the water, sees his image at that place and seeing himself, loves and delights in himself. If he is wise, he will exist moved to love the water rather than himself, for had he not get-go seen himself, he could not have loved or been delighted past himself; nor removed the smudge on his confront revealed to him in the well. Call up of it like this […]: nosotros see neither our dignity nor the defects that mar the beauty of our soul unless we go and look at ourselves in the still sea of the divine Essence wherein we are portrayed; for from it we came when God'due south Wisdom created us to his epitome and likeness (171-172).[ii]

As McDermott explains, when a person comes to the sea (God) and looks into information technology, the starting time step is to observe "how supremely he himself is loved by God." The fact that the person is loved by God is and then arresting that they go along to stare into the water (125). Next, the person "beholds himself in the wellspring of the sea of the divine Essence," and because the sea is so beautiful, the person is moved to love themselves in the body of water (God) and God in themselves. The person understands that they are made in God's image and therefore reflect goodness. This goodness cannot exist apart from the water (God) (125-126). The third pace is "to love the h2o." Past doing this, the person is slowly transformed; "Because love always tends toward union with the honey, the human person'south want for union with God now emerges" (126). As the person becomes immersed in the body of water, they realize that God also desires union with them. The last phase, according to McDermott's recapitulation, is that as the person persists in gazing into the water, they come up to notice their dissimilarity to God. Selfishness has left their face blemished (127). Thus, the soul begins to hate the selfish part of itself and to love more the role that resembles God (127-128).

Water is a substance replete with possible symbolic meanings and is employed in many literal and figurative roles in the Bible. So it is apropos that Catherine chooses to retrieve in these terms. Every bit a child running about the streets of Siena, she no incertitude stared into many a well and fountain, as the city contains a plethora.

Nonetheless, she consistently refers to God as the "mare pacifico."[iii] And information technology was on a trip to Pisa in 1375 that Catherine kickoff saw the Mediterranean, a year before the in a higher place letter was written. Indeed, it seems Catherine constitute nifty inspiration in the bounding main during her travels. Every bit Mary Ann Fatula notes, "The Trinity became for Catherine a 'deep sea' that she sought to enter with all the power of her being: 'The more I enter you, the more than I discover, and the more than I detect, the more I seek you'" (66).[4] In this beautiful chiasmus, quoted from the Dialogue's conclusion (364), we hear resonances of St. Anselm's (1033-1109) Proslogion.[v] And yet, in her letter, Catherine does not seem to articulate Bernard'due south quaternary degree of dearest in her progression. Still, we must ask whether or not the person staring into God, the "peaceful sea," once they have united themselves to God in abandoning cocky-involvement, would be like the human being depicted in what follows, having become immersed in the h2o.

In the chapter titled "Catherine's Wisdom" in Raymond of Capua's vita of St. Catherine of Siena—what is known every bit the Legenda maior—he relates a item discussion between himself and the saint in which she outlines her beliefs concerning love.[vi] Though brief, Raymond tells us that through self-noesis, "The soul that sees its own pettiness and knows that its whole good is to exist found in the Creator forsakes itself and all its powers and all other creatures and immerses itself wholly in Him."[vii] Indeed, the soul directs "its operations towards Him […] never alienating itself from Him, for it realizes that in Him it tin find all goodness and perfect happiness" (86). This same idea, which aptly expresses the progression through Bernard'south first 3 degrees of love, is stated in Catherine's Dialogue and Letters numerous times, merely Raymond continues to relate her argument to describe a fourth degree. Catherine teaches that one time the soul has come to an sensation of God'south beneficence and love, "Through this vision […], increasing from day to day, the soul is so transformed into God that it cannot call back or understand or love or remember annihilation but God and the things of God. Itself and other creatures it sees [and remembers] simply in God" (86).

To this synopsis, Raymond appends an illustration, illustrating for united states Catherine'southward thought. He tells u.s.a. that when a soul has united with God, "it is like a man who dives into the sea and swims under the h2o: all he can run across and touch is water and the things in the water, while, as for anything exterior the h2o, he can neither run into it nor bear upon it nor feel information technology." Furthermore, "If the things outside the water are reflected in it, and so he can see them, simply only in the water and as they expect in the water, and not in whatsoever other way." Raymond finishes his summary of Catherine'south theology of love, as it were, by saying that "This […] is the truthful and proper mode of delighting in oneself and all other creatures, and information technology tin can never lead to mistake, because, being necessarily always governed by God's ordinance, it cannot lead to […] anything outside God, because all activeness takes identify within God" (86). The motion picture that Raymond paints is remarkably similar to St. Bernard's fourth caste of dearest but far more than brilliant and comprehensible to someone existing in an embodied, terrestrial state. Moreover, it is quite clear that both Catherine and Raymond believe that the quaternary degree of love tin can be reached on this earth, in this life, while Bernard shies away from this possibility. Westwardhile Raymond certainly gleans his aquatic imagery from Catherine's letter, his understanding of the 4th degree of dearest—in keeping with Bernard's terminology—stems, in large part, from her Dialogue.[viii] Looking dorsum, with Raymond'due south illustration under our belts, the person standing on the beach in Catherine's letter possesses the possibility of jumping into the bounding main and looking dorsum to shore with a new perspective, viewing the earth, and then, from the contrary vantage bespeak. In all authenticity, what Raymond is doing is combining Catherine'southward teachings into this powerful analogy, integrating what she writes in her letter of the alphabet with the thought she lays out in her Dialogue. He, in essence, glosses her theology of love.

While all hagiographers have their own agenda and will oftentimes bend the life of a holy person to fit sure clerically approved tropes, Raymond is faithful, I think, in this case to the message that Catherine and then desperately sought to express. Merely more than this, he also shows us that Catherine lived according to her theology, even attaining the ultimate degree of dearest. For Catherine, the pivotal movement occurs when the growth of fidelity continues, as Noffke puts information technology, "deepening into friendship and even spousal human relationship with God" (67). This, for Catherine, takes place in Christ's heart—not the mouth, as in much of the commentary tradition on the Song of Songs. While Raymond may often call Catherine the "bride of Christ," this is non the finish of love'southward stages as taught or lived by St. Catherine, nor is it for Raymond. For Catherine, the mouth is used for other purposes—meditation and ministry building.

When the soul has reached the mouth of Christ and excellence, Catherine informs u.s. in her Dialogue that, "she shows this by fulfilling the mouth's functions;" that is, "she speaks […] with the tongue of holy and constant prayer." This tongue possesses a dual expression: interiorly it prays for souls; exteriorly, the oral fissure "proclaims the teaching of […] Truth, admonishing, advising, testifying, without any fear" (140). This is how the man person attains Bernard's fourth caste; they turn from their all-absorbing bail with God back to the world, extending, in their action, the love of God—God himself—in which they now perfectly participate. In its neighbors, the soul is "afforded the ways to do love of God," which then results in a more unitive human relationship with God (Cavallini 142).[ix] Raymond portrays Catherine making this transition at the beginning of the 2nd part of her vita when she is called to a more active life.

Following Catherine'southward gradual entrance into the public arena, she began her acts of charity, commencement merely doing good works for others, and then personally calling people to spiritual conversion—metanoia—likewise as being an example for her followers, so fifty-fifty traveling and settling disputes betwixt whole regions of Europe. As Raymond tells us, "The source and basis of all she did was honey; and and so clemency towards her neighbour surpassed all her other actions" (116). Catherine resisted giving upward her life of solitude to minister to others, simply in the end, she shifted "from a beloved that centered essentially in her own intimate possession of God to a dearest that was approachable and redemptive while still deeply grounded in contemplative prayer" (Noffke 65). In this mode, Catherine managed to fuse the agile and contemplative lives. Catherine progressed from exemplifying Bernard'southward 3rd degree to existence the "Saviour of Souls," seeking "both to unite with God and to serve vigorously her club and church" (Scott 36).[x]

Thus, St. Catherine of Siena lived her own spiritual lessons. Raymond not only skillfully explains Catherine'due south theology of beloved, but also shows us the last progression through Catherine herself. In this way, he makes what Bernard believed unattainable into an, at least possible, reality. Of course, Catherine was an exceptional person, and this lies at the heart of Raymond'south bid for her canonization (384). Having spent so much time together, at that place existed a special symbiosis betwixt Raymond and Catherine, which immune him to understand her in a way that her humility would not. His hagiographic effort points to her doctrine and gives it shape. Just as Catherine interpreted and enhanced St. Bernard's degrees of love, Raymond glosses St. Catherine and brings the progression full circle by property her up as an instance of the 4th degree of about perfect and holy beloved. From humble beginnings and in the confront of patriarchal strictures, Catherine has touched the lives of many and left an indelible mark upon the history of Western Christianity and theological thought. In her own words to Raymond of Capua—in her own hand—she says that God provided her with an aptitude for writing "so that when I descended from the heights [of contemplation], I might have a little something with which I could vent my heart, lest it burst" (Alphabetic character 272).[xi]

Hannah Zdansky, Ph.D.

Academy of Notre Dame

Farther Reading:

Ashley, Bridegroom. "St. Catherine of Siena's Principles of Spiritual Direction." Spirituality Today 33 (1981): 43-52.

Astell, Ann W. Eating Beauty: The Eucharist and the Spiritual Arts of the Centre Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Printing, 2006.

Astell, Ann. "Heroic Virtue in Blessed Raymond of Capua's Life of Catherine of Siena." Journal of Medieval and Early Mod Studies 42 (2012): 35-57.

Catherine of Siena: The Cosmos of a Cult. Ed. Jeffrey Hamburger and Gabriella Signori. Turnhout: Brepols, 2013.

Coakley, John Due west. Women, Men, and Spiritual Power: Female Saints and Their Male Collaborators. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006.

Friedman, Joan Isobel. "Politics and the Rhetoric of Reform in the Letters of Saints Bridget of Sweden and Catherine of Siena." Livres et lectures de femmes en Europe entre Moyen Âge et Renaissance. Ed. Anne-Marie Legaré and Bertrand Schnerb. Turnhout: Brepols, 2007. 279-294.

Gardner, Edmund G. "St. Catherine of Siena." The Hibbert Periodical 5 (1906): 570-589.

Hollywood, Amy. Astute Melancholia and Other Essays: Mysticism, History, and the Written report of Religion. New York: Columbia University Printing, 2016.

Levasti, Arrigo. My Servant, Catherine. Trans. Dorothy Thou. White. London: Blackfriars Publications, 1954.

Luongo, F. Thomas. "Cloistering Catherine: Religious Identity in Raymond of Capua'due south Legenda maior of Catherine of Siena." Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History 3 (2006): 25-69.

Luongo, F. Thomas. The Saintly Politics of Catherine of Siena. Ithaca: Cornell University Printing, 2006.

Mews, Constant. "Catherine of Siena, Florence, and Dominican Renewal: Preaching through Letters." Studies on Florence and the Italian Renaissance in Honour of F. West. Kent. Ed. P. F. Howard and C. Hewlett. Turnhout: Brepols, 2016. 387-403.

Mews, Abiding. "Thomas Aquinas and Catherine of Siena: Emotion, Devotion, and Medicant Spiritualities in the Tardily Fourteenth Century." Digital Philology: A Periodical of Medieval Cultures 1 (2012): 235-252.

Noffke, Suzanne. "Catherine of Siena, Justly Md of the Church?" Theology Today 60 (2003): 49-62.

Noffke, Suzanne. "Catherine of Siena." Medieval Holy Women in the Christian Tradition c. 1100-c. 1500. Ed. A. Minnis and R. Voaden. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010. 601-622.

Tylus, Jane. Reclaiming Catherine of Siena: Literacy, Literature, and the Signs of Others. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing, 2009.

Walsh, Ann. "St. Catherine of Siena: Physician of the Church." Supplement to Doctrine and Life eight (1970): 134-144.

Notes:

[i] For the dating, see Noffke's The Messages, vol. ii, p. two. In what follows, however, I am making utilize of the letter as translated by Kenelm Foster and Mary John Ronayne in I, Catherine: Selected Writings of St. Catherine of Siena. London: Collins, 1980. Suzanne Noffke renders the Italian fonte, which possesses multiple meanings, as the very literal 'fountain.' I think this word would best be translated as 'wellspring,' every bit in Foster and Ronayne's edition, or fifty-fifty 'fount,' both meaning the water itself. 'Wellspring' also amend captures the epitome of Christ as the source of living water (John 4:7-fifteen; seven:37-38).

[ii] Insofar as the h2o acts as a mirror, Catherine'south thinking here shares much with St. Augustine's in De Trinitate (c. 400-416).

[iii] At the end of the Dialogue—after having exclaimed "O completeness! O eternal Godhead! O deep bounding main!"—Catherine concludes her discussion of faith by proverb, "Truly this light is a sea, for it nourishes the soul in you, peaceful bounding main, eternal Trinity. Its water is not sluggish; so the soul is not afraid because she knows the truth. It distills, revealing subconscious things, so that here, where the virtually abundant low-cal of faith abounds, the soul has, equally information technology were, a guarantee of what she believes. This water is a mirror in which you, eternal Trinity, grant me knowledge; for when I look into this mirror, holding it in the hand of dear, information technology shows me myself, every bit your cosmos, in yous, and you in me through the union you have brought about of the Godhead with our humanity" (365-366).

[four] Run into Fatula's Catherine of Siena's Mode. Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, 1987.

[v] Anselm petitions God: "Teach me to seek you, and as I seek you, show yourself to me, for I cannot seek you unless you show me how, and I volition never find you unless you lot show yourself to me. Let me seek you past desiring you, and want you exist seeking you; permit me discover y'all by loving you lot and love you in finding y'all" (243). This language is very similar to the opening of St. Augustine'due south Confessions. For this translation, see The Prayers and Meditations of Saint Anselm with the Proslogion. Trans. Benedicta Ward. New York: Penguin Books, 1973.

[vi] The English translation used is the post-obit: The Life of St. Catherine of Siena. Trans. George Lamb. Rockford, IL: TAN Books and Publishers, Inc., 2003. The work on which this is based is S. Caterina da Siena. Trans. Giuseppe Tinagli. Siena: Cantagalli, 1934, with reference to the Latin Bollandist text of 1860.

[7] On the importance of self-cognition, see Thomas McDermott's "Catherine of Siena's Didactics on Cocky-Cognition." New Blackfriars 88 (2007): 637-648. In short, Catherine views self-knowledge as the cardinal ground of spiritual evolution (643).

[viii] Without a doubt, Raymond was very familiar with the fabric of Catherine's Dialogue, for he quotes it to a nifty extent in i of the later chapters in the vita, titled "For Christ Lonely." In fact, another i of Catherine's messages addressed to him (T272/G90) also recounts some of the aforementioned ideas as establish in the Dialogue.

[ix] See Giuliana Cavallini's Catherine of Siena. London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1998.

[x] See Karen Scott's "St. Catherine of Siena, 'Apostola.'" Church History 61 (1992): 34-46.

[xi] For this letter, run across pp. 538-39 of Le Lettere di Santa Caterina da Siena. Ed. Antonio Volpato, in Santa Caterina da Siena: Opera Omnia. Testi e concordanze. Ed. Fausto Sbaffoni. Pistoia: Provincia Romana dei Frati Predicatori, 2002. The translation is taken from p. 156 of Jane Tylus'south chapter "Mystical Literacy: Writing and Religious Women in Tardily Medieval Italy" in A Companion to Catherine of Siena. Ed. Carolyn Muessig, George Ferzoco, and Beverly Mayne Kienzle. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

St. Catherine Benincasa is one of merely four women to be declared a Md of the Church (Oct. 4, 1970) for her contribution to the understanding of Christian scripture and for her advancement of theology. That said, there has long been discussion of the extent to which Catherine was educated, even literate, given that, as a woman during the Late Middle Ages, formal paths of learning were unopen to her. Born in 1347 into a well-off working-class family of Siena, she showed even as a child an inclination towards the holy life.

Against her parents' preference to see her married, she became a Dominican tertiary at the age of 18. The remaining years of her life were spent in a great deal of action, tending to the poor and sick of her customs besides as travelling to intercede in political disputes, but also lengthy contemplation, with her receiving many visions over her lifetime and the stigmata in 1375. Between this year and her death in 1380, Catherine as well undertook to write a plethora of messages to important figures besides as to those closest to her, these being, in a manner, her outlet for preaching, since, at least officially, women were not allowed to preach (equally they notwithstanding are non in some Christian denominations). These letters, and also her greatest work, her "libro," the Dialogo della divina provvidenza, were nearly all dictated to scribes, which has led some scholars to question the caste of Catherine'south bureau in her output. But the important thing to recall is that this was not an uncommon practice even for men, and nosotros do know that Catherine wrote some letters herself because she tells us this, though these were written in Italian, not the learned Latin of the clerical elite. Catherine, for her part, still, never allow anything deter her. She is perhaps most famously known for marching to Avignon to tell Pope Gregory Eleven to return to Rome, which he did.

Only what of Catherine's continued learning over the years of her ministry building—on her own and through those in her circles—and her intellectual contributions? In that location has been consideration given to her influences in much of the scholarship, but I volition focus on one predecessor that has received limited attending. We know that Catherine was inspired past the besides politically-involved and reformative 12th-century mystic and Dr., St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), because Catherine quotes Bernard in some of her letters.[i] All the same, it is difficult to know how exactly she might accept been exposed to his works and to which ones precisely. Yet, there are striking parallels between her theological thinking and Bernard's, which is something that her confessor and later on hagiographer, Blessed Raymond of Capua (1330-1399), emphasized by means of a metaphor that Catherine herself invented of God as a tranquil ocean.

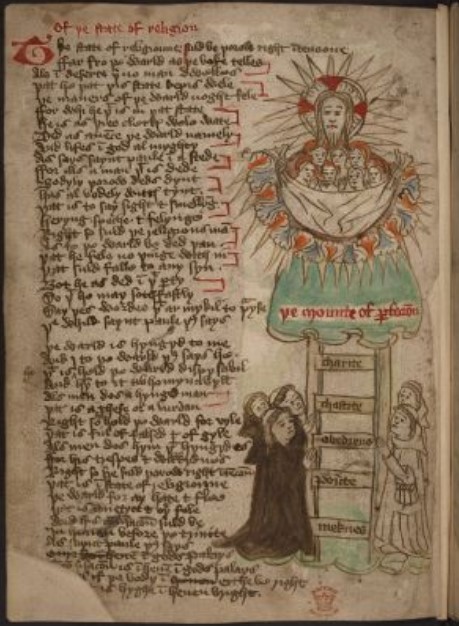

For anyone who has even dabbled in medieval Christian theology and mysticism, it should no doubt have become quickly apparent that a longtime, widespread, major preoccupation is the gradual perfection of the homo volition in a journey towards God and the hope of blissful vision—you know, the catastrophe of Dante'due south Commedia. This ascent of the soul or mind is allegorized using various schemata: ladders or stairs, mountains, trees, the body of Christ, a six-winged seraph, etc. Merely what is central is that this progression occurs by means of specific steps, stages, or degrees (though these differ slightly from text to text) until the human being volition—through the soul's exertion and divine grace working in tandem—becomes and so refined, then like unto God'southward, that the person's will and God'due south get one, and the individual and God are joined in metaphysical union, the stop consequence being what is chosen theosis.[two]

One of the best-known theologians to develop such a schema was St. Bernard of Clairvaux. His offset published work, The Steps of Humility and Pride (c. 1120), employs the epitome of a ladder and gives a rather straightforward and practical account of the vices and deportment that drag one down the ladder, whereas the virtues and behavior prescribed past St. Benedict serve as the counters, leading 1 up. However, Bernard goes into much more conceptual, soteriological detail in his afterwards work, On Loving God (De diligendo Deo) (c. 1126). Herein, St. Bernard describes the degrees of love through which a soul should progress in rather abstract terms without much recourse to figurative language or imagery. He claims that "Since we are carnal and built-in of the concupiscence of the flesh, our cupidity or love must begin with the flesh," simply in gild to achieve salvation, love must advance, "until it is consummated in the spirit" (40).[4] According to Bernard, a person moves from when "human being […] loves himself for himself because he is carnal and sensitive to nothing but himself" (starting time degree) to loving God "for man's sake and not for God's sake," "when he sees he cannot subsist by himself" (xl) (second degree). Because humans are corporeal creatures, the first affair they are able to know and to dear is themselves (25). All the same they begin to motion outwards from themselves when they sense an insufficiency, a lacking. This begins the shift into the second caste when a person realizes that they need something more and searches to beloved outside their existence, but does so for themselves, loving God for the advantage it brings them (27). In Augustinian language, this is yet cupiditas, for ane's love remains focused upon the self.[v]

A dramatic transformation occurs, though, betwixt the second and 3rd degrees. The tertiary is attained when a person "loves God non now because of himself but because of God" (41). That is, a person turns from focusing upon themselves to focusing upon something greater, desiring God not for personal gratification, only out of pure honey. At this point, caritas is accomplished. The 4th degree of love, then, involves a person'due south desires condign superseded past God's when a person comes to love themselves, others, and all of cosmos through God because that is God'south volition, and in reaching the quaternary degree, God's and a person's wills get i (29). Nonetheless, Bernard opines that, "I incertitude if he ever attains the fourth degree during this life, that is, if he always loves but for God's sake" (41). Simply if this were to exist the example, Bernard says it would occur "when the adept and true-blue servant is introduced into his Lord'due south joy, is inebriated by the richness of God'south dwelling. In some wondrous way he forgets himself and ceasing to belong to himself, he passes entirely into God and adhering to him, he becomes i with him in spirit" (41). When a soul thus arrives at the 4th degree, its final destination, information technology must turn back to the world through God just as a pilgrim must return to his or her point of origin, simply in both cases, the person has been utterly changed through their experiences, acquiring a radically different outlook. However, the attitude that St. Bernard expresses here is that the fourth degree is catchy. Indeed, it requires much of the homo person, forgoing ane's will completely and adhering entirely to God.

St. Catherine conceives of a like progression in her Dialogue, but she makes use of a common devotional image—the torso of Christ.[vi] She is also more positive in her hopes for humanity, but her indebtedness to Bernard's thinking should become abundantly clear, since she too presents a pilgrimage of honey, which, every bit Bernard would say, "advances by stock-still degrees, led on by grace" (xl). According to Catherine's schema, the journeying begins in a river below a concrete bridge, which is Jesus Christ, the ontological and moral Bridge joining Heaven and world.[7] Hither, a person is trying to forge their way beyond the swift water into Paradise without consideration for God. But for this reason, they will never succeed (67). Suzanne Noffke, the text's translator, refers to this stage as "slavish" love because the person is a slave to sin out of honey for themselves, and even if they begin to plough to God, the regard remains servile out of fear of punishment (67).[viii] I believe this best fits Bernard'south first caste of love. Every bit Mary Ann Follmar explains more concisely in her commentary, God, with ineffable dearest, sends the soul gifts, hoping that it volition ameliorate recognize the true source of its blessings. If this does not work, then God allows the winds of arduousness to blow, abetting self-reflection (6-7).[ix] Should all go well, according to the Dialogue, the person will realize that everything they have is from God, and due to this, they volition be moved to honey with a mercenary love, that is, for the profit they can derive from God (113). The mercenary love enacted at the feet of Christ the Bridge exemplifies Bernard'south 2d degree (Catherine'due south first).

Equally the person'south angel go along to be ordered through self-noesis, which inextricably entails knowledge of God, they progress to the side of Jesus through which they enter into Christ's heart via his side wound.[10] In the backbreaking climb to Christ'southward side, the person becomes a "good and faithful servant," simply as selfishness diminishes farther, they become Christ's friend and pass into his middle (64, 115). Follmar clarifies that, "The opening in the heart signifies intimacy of amore and confidence," which can only exist between close friends. When someone loves like a friend, they exercise and then without respect for themselves; the person now "loves virtue and every good solely for love of God" (45). This is why they can now feel Christ's hugger-mugger, "the manifestation of divine love," symbolized by the claret poured along from Christ's eye upon the cantankerous (46). By reaching the phase where the will of the person has dissipated and is being replaced with God's, the heart of Christ becomes the person's own heart. This, I think, is Bernard's tertiary degree but Catherine's second.

By way of the center, the pilgrim and so travels to Christ'southward oral cavity. Here, the love has go more than just friendship; at present it is also filial. In this last stage, in the words of God to Catherine, the person "loves me for myself, because I am supreme Goodness and deserve to exist loved, and she loves herself and her neighbors because of me, to offer glory and praise to my name" (141). The destination of the oral fissure signifies for Catherine the third and quaternary stages of the soul, which seem to represent Bernard's fourth degree. The distinction Catherine makes is that embracing the world through God and learning to love God in one's neighbor and self (third) leads to an even more than perfect marriage with God (4th). Perfect honey is achieved in the heart of Christ, but "(most) perfect love," every bit Thomas McDermott dubs it, is attained at the 3rd step, which necessarily leads to the greatest matrimony with God that can be achieved (183-193).[xi] The ultimate end of the journey is to come up to the gate on the other side of the Bridge that leads into Paradise, merely the threshold may non be crossed while alive. Notwithstanding, Catherine, functioning every bit God'south mouthpiece, tells us that,

For once souls take risen up in eager longing, they run in virtue forth the bridge […] and make it at the gate with their spirits lifted up to me. When they accept crossed over [the bridge] and are inebriated with the blood and aflame with the fire of dearest, they taste in me the eternal Godhead, and I am to them a peaceful sea with which the soul becomes then united that her spirit knows no movement but in me. Though she is mortal, she tastes the reward of the immortal (147-148, my emphasis).

And if the nonetheless living pilgrim and so turns back to the globe through God, she or he can alive out Bernard's fourth degree.

McDermott notes that, "the peaceful sea is […] an image of the soul'due south destiny, that of ultimate union with God," and he is certainly correct (199). But we need to examine this metaphor a bit more closely because information technology is one that Catherine, too every bit Raymond of Capua, rely upon a great bargain. And while Catherine's use of Christ'southward trunk as an allegorical roadmap, of sorts, is helpful, specially with regard to eliciting an affective response, it as well remains abstruse from the standpoint of human experience. How tin a person, in the flesh, truly conceive of something like the fourth degree of love, conceive of being and so united to God that one's entire existence—one'due south reality—is mediated through God? In short, how can we conceive of theosis?

Hannah Zdansky, Ph.D.

Academy of Notre Dame

[i] One example is in a alphabetic character to the Abbess of Santa Marta in Siena. See p. 52 of vol. one of The Letters of Catherine of Siena. 3 vols. Trans. Suzanne Noffke. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2000. Kenelm Foster notes that some twoscore such citations take been identified in the Letters. See p. 312 of "St. Catherine's Pedagogy on Christ." Life of the Spirit 16 (1962): 310-323.

[ii] It must be said, though, that Western theologians are often a flake more than skeptical of the possibility of theosis than Eastern Christian thinkers, an example of which pessimism we can meet in St. Bernard'southward piece of work in what follows.

[three] More information as well equally the entire digitized manuscript tin be found here: http://world wide web.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_37049. For an first-class study, see Jessica Brantley's Reading in the Wilderness: Private Devotion and Public Performance in Late Medieval England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

[iv] For this translation, come across On Loving God. Trans. Emero Stiegman. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, Inc., 1995. For an edition of the text, come across Liber de diligendo Deo. Sancti Bernardi opera. vol. 3. Ed. J. Leclercq and H. One thousand. Rochais. Rome: Editiones Cistercienses, 1963. 119-154.

[v] Bernard'southward understanding of charity and cupidity is very much reliant upon St. Augustine of Hippo'south (354-430). See especially Augustine's De doctrina christiana (c. 396-427), specifically Bk. 3, Ch. ten, § xvi, which is on p. 88 of the following translation: On Christian Doctrine. Trans. D. West. Robertson, Jr. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997. For an edition, see De doctrina christiana. Ed. J. Martin. Corpus Christianorum: Serial Latina. vol. 32. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 1962. 1-167.

[vi] It is quite possible that Catherine was also inspired to use this prototype through St. Bernard's 3rd and 4th sermons on the Song of Songs. Run into On the Vocal of Songs I. Trans. Kilian Walsh. Spencer, MA: Cistercian Publications, 1971.

[seven] The translation used throughout is the following: The Dialogue. Trans. Suzanne Noffke. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Printing, Inc., 1980. For an edition, come across Il Dialogo della Divina Provvidenza ovvero Libro della Divina Dottrina. Ed. Giuliana Cavallini. Rome: Edizioni Cateriniane, 1968.

[viii] See Noffke's volume Catherine of Siena: Vision through a Distant Eye. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1996.

[ix] See Follmar'south The Steps of Love in The Dialogue of St. Catherine of Siena. Petersham, MA: St. Bede's Publications, 1987.

[x] Heather Webb mentions that St. Bernard of Clairvaux was one of the first to state definitively that the spear which pierced Christ's side reached all the fashion to his heart (805). See "Catherine of Siena'southward Heart." Speculum 80 (2005): 802-817.

[xi] Come across McDermott's Catherine of Siena: Spiritual Development in Her Life and Teaching. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, Inc., 2008.

Appendix:

| St. Bernard of Clairvaux'due south Degrees of Love (De diligendo Deo) | St. Catherine of Siena's Degrees of Beloved (Dialogo della divina provvidenza) |

| 1. Man loves himself for his own sake: "man start loves himself for himself considering he is carnal and sensitive to nothing but himself" (40). | 0. The River of Sin – Slavish Beloved: "Only those who do not keep to this mode travel below through the river […]. And since in that location is no restraining the water, no one can cantankerous through it without drowning. Such are the pleasures and weather condition of the world. Those whose honey and desire are not grounded on the rock but are set without order on created persons and things apart from me […] run on just as they do" (67). "Open up your heed's eye and wait at those who drown by their own choice and see how they have fallen by their sins. […] they have become servants and slaves of sin. I made them trees of love through the life of grace […]. Just they have become trees of expiry, because they are dead. Do you know where this tree of decease is rooted? In the superlative of pride, which is nourished by their sensual selfishness" (73). "You know that every evil is grounded in selfish love of oneself" (103). |

| 2. Man loves God for his own benefit: "when he sees he cannot subsist past himself, he begins to seek for God by faith and to love him every bit necessary to himself. Then in the second degree of dear, human loves God for man's sake and not for God's sake" (twoscore). | 1. The Feet of Jesus – Mercenary Love: "There are others who get faithful servants. They serve me with love rather than that slavish fright which serves only for fear of penalty. Just their love is imperfect, for they serve me for their own turn a profit or for the delight and pleasure they find in me" (113). "They love their neighbors with the aforementioned love with which they beloved me—for their own profit" (114). |

| iii. Man loves God for God'due south sake: "When man tastes how sweet God is, he passes to the tertiary degree of beloved in which homo loves God not now because of himself but because of God" (41). | 2. The Wounded Side of Jesus – Love of Friendship: "If yous dear me the mode a servant loves a master, I as your principal will give you lot what you have earned, but I will not show myself to you lot, for secrets are shared only with a friend who has go one with oneself. Still, servants can grow because of their virtue and the love they bear their primary, even to becoming his very dear friend. And then it is with these souls. As long as their love remains mercenary, I exercise non testify myself to them. Only they can, with contempt for their imperfection and with love of virtue, utilise hatred to dig out the root of their spiritual selfishness. They can sit down in judgment on themselves so that motives of slavish fright and mercenary love practice non cross their hearts without existence corrected in the lite of most holy faith. If they act in this style, information technology will delight me much that for this they volition come up to the beloved of friendship. And then I will show myself to them, just as my Truth said: 'Those who love me will be one with me and I with them, and I will evidence myself to them and we will make our dwelling place together.' This is how it is with very love friends. Their loving affection makes them ii bodies with one soul, because love transforms one into what 1 loves" (115-116). |

| 4. Homo loves himself for the sake of God: "Happy the man who has attained the fourth degree of honey, he no longer fifty-fifty loves himself except for God" (29). "man remains a long fourth dimension in this [tertiary] degree, and I doubt if he ever attains the 4th caste during this life, that is, if he ever loves just for God'south sake" (41). "No doubt, this happens when the good and faithful servant is introduced into his Lord's joy, is inebriated by the richness of God's domicile. In some wondrous way he forgets himself and ceasing to belong to himself, he passes entirely into God and adhering to him, he becomes one with him in spirit" (41). | 3. The Mouth of Jesus – Filial Honey: "At present this is how the soul acts who has in truth reached the 3rd stair. This is the sign that she has reached it: Her selfish volition died when she tasted my loving charity, and this is why she establish her spiritual peace and quiet in the mouth. […] She has let go of and drowned her ain will, and when that will is expressionless, at that place is peace and repose" (141). "She brings along virtue for her neighbors without pain" (141). "she loves me for myself, considering I am supreme Goodness and deserve to be loved, and she loves herself and her neighbors because of me, to offering glory and praise to my proper noun" (141). "Later on she has come up to perfect, free dearest, she lets go of herself and comes out […]. And this brings her to the fourth stage. That is, later the third stage, the stage of perfection in which she both tastes and gives birth to charity in the person of her neighbor, she is graced with a final stage of perfect union with me. These two stages are linked together, for i is never found without the other any more than charity for me can exist without charity for one'south neighbors or the latter without charity for me. The one cannot be separated from the other. However, neither of these two stages can be without the other" (137). |

fredricksenyournegand.blogspot.com

Source: https://sites.nd.edu/manuscript-studies/tag/catherine-of-siena/

0 Response to "Catherine of Siena Levels of Glory if a Man Could See Heaven He Would Never Sin Again"

Post a Comment